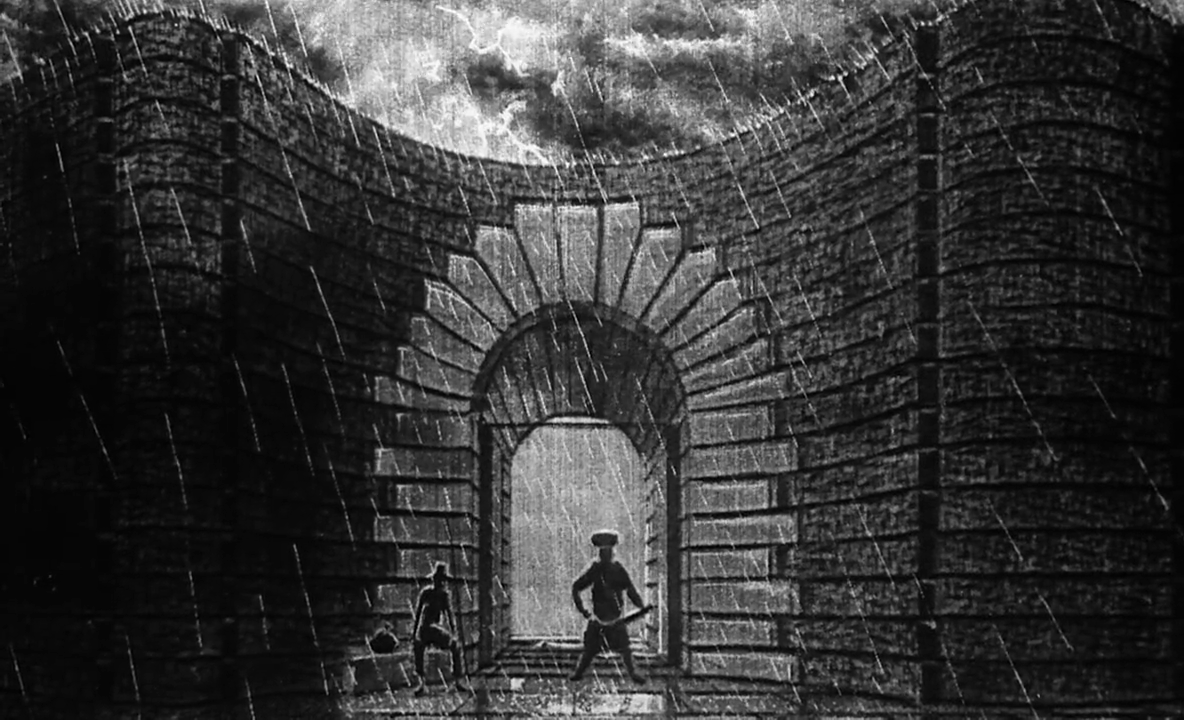

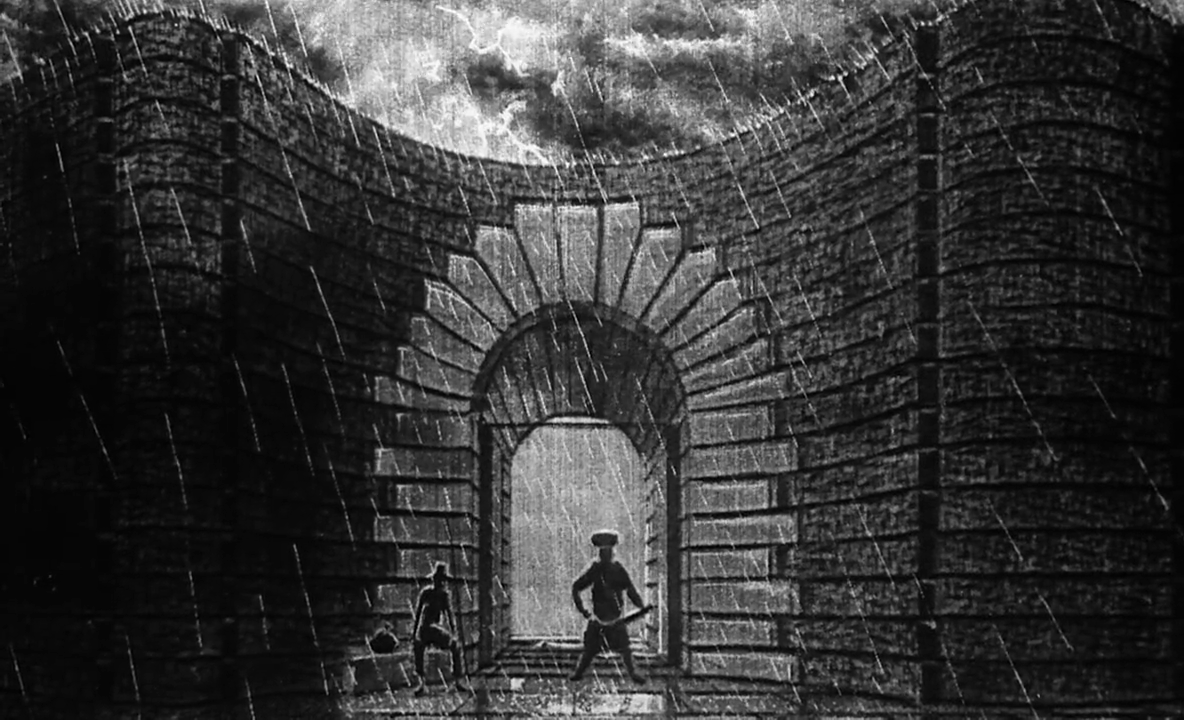

Before the Law stands a doorkeeper on guard. To this doorkeeper there comes a man from the country who begs for admittance to the Law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot admit the man at the moment. The man, on reflection, asks if he will be allowed, then, to enter later.

‘It is possible,’ answers the doorkeeper, ‘but not at this moment.’

Since the door leading into the Law stands open as usual and the doorkeeper steps to one side, the man bends down to peer through the entrance.

When the doorkeeper sees that, he laughs and says: ‘If you are so strongly tempted, try to get in without my permission. But note that I am powerful. And I am only the lowest doorkeeper. From hall to hall keepers stand at every door, one more powerful than the other. Even the third of these has an aspect that even I cannot bear to look at.’

These are difficulties which the man from the country has not expected to meet; the Law, he thinks, should be accessible to every man and at all times, but when he looks more closely at the doorkeeper in his furred robe, with his huge pointed nose and long, thin, Tartar beard, he decides that he had better wait until he gets permission to enter. The doorkeeper gives him a stool and lets him sit down at the side of the door. There he sits waiting for days and years. He makes many attempts to be allowed in and wearies the doorkeeper with his importunity.

The doorkeeper often engages him in brief conversation, asking him about his home and about other matters, but the questions are put quite impersonally, as great men put questions, and always conclude with the statement that the man cannot be allowed to enter yet. The man, who has equipped himself with many things for his journey, parts with all he has, however valuable, in the hope of bribing the doorkeeper.

The doorkeeper accepts it all, saying, however, as he takes each gift: ‘I take this only to keep you from feeling that you have left something undone.’

During all these long years the man watches the doorkeeper almost incessantly. He forgets about the other doorkeepers, and this one seems to him the only barrier between himself and the Law. In the first years he curses his evil fate aloud; later, as he grows old, he only mutters to himself. He grows childish, and since in his prolonged watch he has learned to know even the fleas in the doorkeeper’s fur collar, he begs the very fleas to help him and to persuade the doorkeeper to change his mind.

Finally his eyes grow dim and he does not know whether the world is really darkening around him or whether his eyes are only deceiving him. But in the darkness he can now perceive a radiance that streams immortally from the door of the Law. Now his life is drawing to a close. Before he dies, all that he has experienced during the whole time of his sojourn condenses in his mind into one question, which he has never yet put to the doorkeeper.

He beckons the doorkeeper, since he can no longer raise his stiffening body. The doorkeeper has to bend far down to hear him, for the difference in size between them has increased very much to the man’s disadvantage.

‘What do you want to know now?’ asks the doorkeeper, ‘you are insatiable.’

‘Everyone strives to attain the Law,’ answers the man, ‘how does it come about, then, that in all these years no one has come seeking admittance but me?’

The doorkeeper perceives that the man is at the end of his strength and that his hearing is failing, so he bellows in his ear: ‘No one but you could gain admittance through this door, since this door was intended only for you. I am now going to shut it.’

by Franz Kafka